|

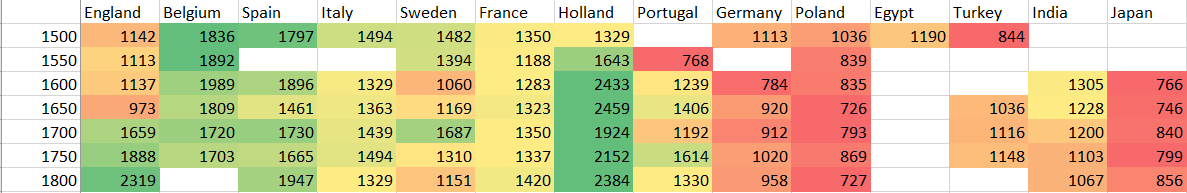

16/10/2019 The Crucial CenturyIf a peaceful extraterrestrial visited the world in 1550, I often wonder where it would see as being the most likely site of the Industrial Revolution – an acceleration in the pace of innovation, resulting in sustained and continuous economic growth. So many theories about why it happened in Britain seem to have a sense of inevitability about them, but our extraterrestrial visitor would have found very few signs that it would soon occur there. There were many better candidates, on a multitude of metrics. Our visitor might first have searched for well-populated hubs. There are mountains of research on the importance of cities for innovation and economic growth. But the most urbanised area in 1550 was what would eventually become present-day Belgium, with almost a quarter of its population living in cities. The areas now corresponding to the Netherlands, as well as Italy and Spain, all had urbanisation rates of over 10%. By contrast, only 3.5% of the population of England and Wales lived in cities, with likely fewer in Scotland. Britain would not have looked promising. Of course, the size of the country also matters when measuring urbanisation - Belgium is a lot smaller than Spain. But if our visitor looked instead for the largest cities, then Britain’s largest urban centre, London, would also have barely registered. At about fifty to seventy thousand inhabitants in 1550, it was dwarfed by Beijing and Constantinople, both about ten times as large. There were many more huge cities in China, but in Western Europe alone, both Paris and Naples were also at least three times larger than London. Nonetheless, our visitor might also have looked at places that were already quite wealthy. Some historians argue that Britain’s precocity hinged on it building upon prior wealth or high living standards, derived from any number of sources – skills, trade, agriculture, or conquest. Britain’s eventual success, when viewed through this lens, can appear to be the inevitable product of accumulating capital to spend on technological experimentation; or of a commercial hub being inspired by the newly-imported products of west and east; or of a less malnourished and potentially smarter population simply achieving its potential. But England in 1550 was by global standards quite poor. Historical GDP per capita measures are notoriously difficult to obtain, even for some countries in the twentieth century let alone the sixteenth. The historical GDP per capita of England – by far the most studied region – is still hotly debated among economic historians. Nonetheless, according to the most recent collection of estimates – the Maddison project’s database of 2018 – in 1550 our extraterrestrial visitor would have been much more interested in Belgium. England at that stage lagged behind almost all of the areas for which we have estimates: Holland, Spain, Italy, Sweden, and France. In 1600, it was behind Portugal and India. Here are the figures in 2011 dollars; the colours are by row: Such estimates should of course be taken with a hefty boulder of salt. (Note, also, that these particular figures, called "CGDPpc", are something of an innovation by the team compiling the Maddison Project Database - they use multiple benchmarks to improve how we compare countries' relative incomes in any particular year, which comes at the cost of not being able to compare their growth rates, for which there are separate figures. In other words, you should read the figures by row, not by column.) But it is worth noting that the more recent research on historical GDP per capita, finally filling in some details for regions other than England and Holland, often results in those other countries seeming richer in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The more we know, the more the traces of an early English divergence seem to disappear. Even without access to such statistics, however, our visitor would have noticed that in the mid-1550s England suffered severe food shortages. Indeed, the threat of famine would be present right up until the beginning of the eighteenth century: there was a major famine in the north of England in 1649, and even a famine in the 1690s that killed between five and fifteen percent of Scotland’s population. Britain would one day become perhaps the first famine-free region, but that did not occur until much later, when innovation had already begun to accelerate. It may even have been its result. And England in 1550 was not just poor; it was also weak. If our visitor thought, as some historians do, that conquest and exploitation were essential for future growth, then it was Spain that had the major overseas empire, followed by Portugal. England in 1550 had no colonies in the New World, and its attempts to found them all failed until the seventeenth century, by which stage the Dutch and French had also begun to extend their own empires too. It was not until the eighteenth century that Britain began to exceed them. In fact, England in 1550 was not even close to being Europe’s preeminent naval power. It was Hispania, not Britannia, who ruled the waves. Even on maps made in England and for the use of the English government, the ocean off the west coast of England and to the south of Ireland was labelled The Spanish Sea. The foreign maps agreed. The North Sea, too, was the Oceanus Germanicus, or German Sea. It gives an idea of who controlled what. And England of course came close to catastrophe in 1588, when the Spanish decided to launch an invasion – although English ships did manage to inflict an initial defeat on the Spanish fleet, it was largely destroyed by the weather. Despite having always been on an island, English policymakers only seriously began to appreciate Britain’s geographical potential for both defence and commerce in the late sixteenth century. Overall, had the size or power of the state been the important factor in causing sustained economic growth, then the more likely candidate in 1550 would have been France. In terms of total annual tax revenues, France’s state was over four times the size of England’s. The states of Spain, the Ottoman Empire, and even teeny tiny Venice raked in more. And when we account for England’s low population, its performance in terms of tax revenue per capita was similarly poor. In the early 1600s the Dutch Republic collected twice as much tax as England, despite being less than half as populous. England only overtook France in per capita terms in the early 1700s, and even then still lagged far behind the Dutch. So Britain’s precocity would have seemed unlikely in 1550. But the exercise potentially also gives us a few clues as to what was important for growth. Indeed, 1550-1650 increasingly appears, to me, to be the crucial century. It was by 1650, for example, that a critical mass of influential inventors and scientists in England were already plotting the creation of what would become the Royal Society – one of the most important institutions in Europe for the promotion of useful technical and scientific knowledge. And it was by 1650 that London had become one of Europe’s largest cities, a major trading centre, and a hub of innovation. More on that another time. --- If you enjoyed reading this, please do share it! To keep up to date with my writing and research and more, sign up to my newsletter.

29 Comments

I’ve spent a lot of time recently thinking and writing about the role of innovators as cultural entrepreneurs — in other words, how it is that innovators themselves created the institutions that would support innovation. It’s an especially important question when considering the origins of modern, innovation-led economic growth, which had appeared in Britain by the mid-eighteenth century.

The cultural entrepreneurship of innovators often took the form of creating entirely new organisations. Take the Royal Society, which in its early years in the 1660s attempted to promote practical technologies as well as what we would now call science. Its founders attempted to collect a dictionary of artisans’ techniques and machines, for example, although many of the artisans were unhappy about their trade secrets being revealed and the project was dropped. Or take the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce, which since 1754 has acted as a voluntary, subscription-funded, and semi-official national improvement agency, in any and every way imaginable. In its first century it provided cash prizes or honorary medals for unpatented inventions, thus revealing the artisans’ trade secrets to the public by purchasing them. (By the way, I recently finished writing a book on the history of the Society of Arts, to be published by Princeton University Press in April 2020). Both the Royal Society and the Society of Arts were created by people who were already innovators. They are very concrete examples of innovators creating the institutions to support innovation. Yet innovators also acted as cultural entrepreneurs in much more humdrum ways. Like any entrepreneurs, cultural or otherwise, they attempted to cater their products to what they thought people would buy. In other words, as innovators, they promoted their inventions in ways that would make invention in general more popular. And one of the ways they did this throughout the period of the British Industrial Revolution was to downplay the effects of technological unemployment — of machines stealing people’s jobs. Some great examples of this downplaying come from patent petitions. A lot of people assume that just because people took out patents for inventions in the eighteenth century, that these were similar to those used today. Patent systems, for example, are often considered better than prizes because they do not seek to dictate the direction of invention — they allow for almost all and any kinds of inventions to be rewarded. But in the early eighteenth century this was not quite the case. Since the Statute of Monopolies of 1624, the monarch was limited in some important ways in terms of the patents they were allowed to issue. The Statute provided a sort of check-list for the law officers (the attorney-general and/or solicitor-generals) to work out whether the patent that an inventor was petitioning for would be legal. The law officers would only recommend an invention for a patent if it passed all the checks. Yet one of the conditions in the Statute was that the invention be “not generally inconvenient”. This very vague condition was usually explained by legal theorists with the example of technological unemployment— that there was once a fulling mill invented for making bonnets and caps, which would have replaced the work of 80 labourers. The mill was thus both undeserving of a patent and then even banned. So not only were the legal conditions for a patent vague, and thus often at the discretion of the law officers to interpret, but they were stacked against labour-saving inventions. At some point in the 1760s the law officers became a lot more lenient about enforcing the conditions of the Statute of Monopolies — they more or less abrogated all responsibility, choosing to simply grant the patent and leave it to others to challenge their legality in court. We don’t really know why they became a lot more laissez faire, or even exactly when. But that’s a story for another time (I’m still in the process of researching some details). Suffice to say, prior to the 1760s there was a bias against labour-saving inventions. And so, it was incumbent on inventors petitioning for patents to allay fears that their inventions would cause unemployment. Thus,Thomas Lombe justified his famous 1718 engines for winding, spinning, and twisting silk, which his brother had stolen from Piedmont, by arguing in his patent petition that they would employ “many thousand families of our subjects”. Why? Because they would also introduce a manufacture not currently already practised in England. Lewis Paul, another major pioneer of mechanising textile manufacture in the early eighteenth century, in 1748 justified his wool-carding machine by saying it was “adapted to the strength and abilities of children”, and would thus allow them “to get a comfortable livelihood”. He focused on the fact that it would employ an otherwise unemployed demographic — kids — rather than saving on the labour of adult workers. In a similar vein, Martin Bedwell in 1729 patented an engine for spinning and weaving hemp, flax, and hair, claiming that it was “so contrived that the invalids in the hospitals, forts, guards, and garrisons may be employed in spinning and weaving linen cloth for tents, sails, sheeting, and shirting”. It would put the idle hands of sick and wounded soldiers to good use, and would apparently save many hundreds of thousands of pounds per year in imports (this was another favourite theme among policy-makers, who were anxious about gold and silver leaving the country to pay for foreign goods). And these themes were not only limited to petitioning for patents. The Society of Arts, for example, offered a prize to anyone who could introduce the making of artificial flowers from point lace (also to replace foreign imports). They noted that it might employ women of middling rank “who at present are supported by their relations, or struggle with difficulties from the smallness of their fortunes”. It was thus not only unemployed kids and the wounded who were to be put to work rather than replacing existing labourers, but also the kinds of women you find as heroines in Jane Austen novels. The person who suggested the prize, a milliner named Dorothy Holt, said she had already instructed a few “young gentlewomen” in the art. Lastly, it’s worth noting labour-saving innovations that were motivated by boredom — the kind of labour that surely everybody would be in favour of eliminating. Take John Napier, for example, a sixteenth-century Scottish lord and the inventor of logarithms. He argued that complex multiplications, divisions, and working out the square and cubical extractions of large numbers “molest and hinder calculators … which besides the tedious expense of time, are for the most part subject to many slippery errors.” Calculators were not the devices of today, but the people who used to be employed to do calculations by hand, usually for astronomical charts, astrological prediction calendars, and so on. The invention of logarithms was thus highly popular among mathematicians who had to do such tedious work — it allowed them to do it faster and with fewer errors. Similarly, Charles Babbage was employed as a “computer” in the nineteenth century when he famously wished aloud that the calculations could all be done by steam. Thus were conceived his Difference Engine and Analytical Engine, the respective ancestors of the modern calculator and computer. Yet by Babbage’s time, things had already dramatically changed in Britain. Policy-makers and many elites were relaxed about technological unemployment, at least as compared to the early eighteenth century. Indeed, when the Luddites started smashing up machinery in the 1810s, the state had no qualms about suppressing them with violence. The seeds of persuasion, sown by the early eighteenth-century innovators, had by the 1800s grown deep roots. 27/9/2017 Why study Economic History?Today I gave the first lecture for a new course I’m teaching at King’s College London, The World Economy and its History. It’s a compulsory first year course for a brand new BSc in Economics. Which means they will be getting an exceptionally well-rounded Economics education, including, in other modules, the evolution of economic theories from Smith through to Marx, Hayek, Keynes and others. It’s a degree I’m very excited to be a part of. Here is what I told my students in the opening lecture about why studying Economic History is worthwhile. It’s rather grandiose, but I hoped to get them excited to study a topic that I personally find so enthralling: What is Economic History? It is about asking some of the biggest and most interesting questions imaginable. Why are we, today, so rich compared to our ancestors? Why are some countries so rich and others so poor? Why were a handful of European countries able to conquer much of the rest of the globe? Those are just a few of the questions we will explore this year, together. Tyler Cowen asks whether the world would have seen an Industrial Revolution if Britain had failed to have one. I’m going to take “Industrial Revolution” to really mean a sustained acceleration of innovation, which is, after all, the underlying source of sustained economic growth.

So let’s assume that Britain had no innovators whatsoever — every single one of the 1,452 individuals whose biographies I lovingly reconstructed over the past few years simply never became innovators. Thomas Newcomen remained an unremarkable iron merchant. Josiah Wedgwood merely copied the tried and tested methods of making ceramics. Sarah Guppy took no interest in her husband’s business affairs. Britain in the eighteenth century might have remained an unremarkable, relatively impoverished nation. But innovation would almost certainly have accelerated elsewhere, probably within the space of a few decades. Britain might have had more innovators, but it did not have a monopoly on them. In fact, we don’t actually know for sure if Britain did have more innovators. It’s possible that an equal number of Dutch and French and German and other countries’ innovators were simply engaged in improving industries that would prove to be less productive. French and Italian innovators mechanised silk-throwing long before the British mechanised cotton-spinning, but cotton for a number of reasons had all the makings of a mass-consumption item (its demand elasticity was much higher). The truth, is we don’t know for sure — nobody, to my knowledge, has yet attempted to put together samples of innovators comparable to those assembled for Britain (don’t worry, I’m working on it..) Soon after I completed my PhD thesis I actually began to compile an equivalent French list (this has recently been on hold, and a Dutch list will also soon be in the works). We know that there were plenty of French innovators — Jacquard, Girard, Montgolfier, Lavoisier, Daguerre all immediately spring to mind — but I didn’t realise quite how many there were until I started to list them. Even my cursory look suggests that Britain may not have been quite as dominant an innovator as we assume. As Joel Mokyr has suggested, Britain’s advantage may have been in adopting and adapting the innovations of others, not necessarily in originating them. (For what it’s worth, I still suspect Britain had more innovators, just not that many more; but again, we don’t yet have the evidence to confirm this suspicion). So if not Britain, probably France. Or the Low Countries, or Switzerland, or the United States. These countries were, after all, the first to experience their own accelerations of innovation either contemporaneously with Britain, or only a few decades after. The raw materials were there. France for example had access to the Atlantic economy, and Belgium had plenty of coal (which France could have imported, or perhaps even conquered). Indeed, as demonstrated by Leonardo Ridolfi’s astonishingly thorough doctoral thesis, the French were a lot richer before 1789 that we had thought. What’s more, France certainly had the scientific knowledge-creation necessary to some of the major technological developments. Denis Papin first became interested with using vacuums to produce motive power during his time in Paris, working with Christiaan Huygens (pronounced like this) and Gottfried Leibniz. These experiments, along with his later work in Germany, eventually led to the first atmospheric steam engines. Such Enlightened thinkers and makers were not just concentrated in Paris, but were spread across the country, as indicated by the work of Squicciarini and Voigtländer. They showed, controlling for for prior development and for mass education, that places with more subscribers to the Encyclopédie tended to develop faster. But this isn’t to say that France (as well as the other countries I’ve mentioned) would have experienced an acceleration of innovation that was quite as fast as that in Britain. There were a number of factors that may have slowed France’s acceleration (but crucially not stopped it):

So without the British acceleration of innovation, the Industrial Revolution would likely have happened elsewhere within a few decades. France and the Low Countries and Switzerland and the United States were by the eighteenth century well on their way towards sustained modern economic growth. The growth would probably have been slower, it may have been delayed. The path that technology took may have been a little more winding. But the improving mentality was already spreading rapidly throughout Europe, as was the commitment to spreading it further. The steam locomotive had already bolted. 4/5/2017 How to Innovate as an ArtistMuch of my work focuses on how more and more people in Britain in the eighteenth century sought to improve technological processes and create more valuable products, thereby becoming innovators. They each received, in my view, an improving mentality: everywhere, and anywhere, they saw room for improvement. But I’m often asked whether innovators also tried to improve fields other than technology.

The answer is certainly yes. Take William Fairbairn, later an inventor of machinery. Fairbairn, when just a teenager, developed a crush on a girl in a nearby village and tried to reverse-engineer the correspondence published in a magazine between two lovers, so as to better flirt with her. He worked methodically, reading a published letter, sketching out a reply, and then comparing it to the reply that was published. Thus, he later recounted, he tried to make romance “subservient to the means of improvement”. Another favourite example is that of William Cecil, inventor of a working internal combustion engine (as early as 1820), as well as of telescopes, animal traps, ear trumpets, and a tool for drawing teeth. But Cecil’s non-technological improvements were to his work as a vicar. He tried to improve the quality of hymns, for which he compiled detailed lists of tunes, and for which he devised a system to classify their quality: A) a style pure, grave, ecclesiastical (first rate / very good / good) B) a style solid, lively, and popular (very good / good / common) C) a style lax, vulgar or secular (popular and pleasing / passable / inferior) The work of a clergyman does not seem amenable to improvement. After all, improvement implies that there is a known function that may be performed better. It is goal-oriented. A machine, for example, may work faster, more precisely, more consistently, more durably, at a larger scale, or at a cheaper cost. When applied to technology, what counts as improvement is usually quite obvious. The quality of hymns, on the other hand, seems too subjective. People differ as to what counts as being “better”. The problem applies to literature, to poetry, or to art. There is technique, to be sure — the precision of a brushstroke, the consistent mixing of a colour — but the overall quality of a work may be assessed by too many different standards, some of them perhaps contradictory. Improvement cannot easily be distinguished from mere variation. Nonetheless, this problem did not stop people from trying. The portrait painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (self-portrait above), in a series of lectures to the Royal Academy of Arts, which he founded, set out an ambitious program for how art was to be improved. The basic foundation was technique, the mechanical dexterity that was necessary to the implementation of designs. But it was in the second and third steps that Reynolds began to grapple with the problem of what counts as improvement. He recommended that artists “amass a stock of ideas, to be combined and varied as occasion may require”. Thus, the new artist was to build up an arsenal of ideas that could later be relied upon when striving for forms that were better: “Invention, strictly speaking, is little more than a new combination of those images which have been previously gathered and deposited in the memory”. But this collection of ideas had another, more important purpose: only by learning from old masters would new artists be able to form a sense of what was more perfect. The aim was to draw together “those perfections which lie scattered among various masters”, to “know and combine excellence”, so as to be “united in one general idea”. Reynolds did not recommend any particular forms or flourishes — the idea or sense of what was better had to be acquired tacitly , by “long and laborious comparison”. Yet he did set out some guidelines for how and what to study. New artists were not simply to copy others, but to learn how to select and discern what was better about them. And new artists would learn best from the old masters, not the recent: “the duration and stability of their fame is sufficient to evince that it has not been suspended upon the slender thread of fashion and caprice, but bound to the human heart by every tie of sympathetic approbation”. Study of the old masters was the way to cut through the temporary fads, to get to the heart of what timelessly and universally captures the imagination. After long and careful study, the artist would appear inspired — “supposed to have ascended the celestial regions, to furnish his mind with this perfect idea of beauty”. Only then, according to Reynolds’s program, could the artist finally recognise what counts as an improvement. Only then could art be improved. |

To keep up to date with my writing and research, sign up to my newsletter.

Recent & Favourite PostsHow innovators defended labour-saving technology

Innovators were often cultural entrepreneurs, having to defend the nature of their innovations in order to find social acceptance for them. Is Innovation in Human Nature? A summary of one the major findings from my research into the Industrial Revolution. The upshot: it is not. If not Britain, where? The case for a French Industrial Revolution. If Britain had not existed, it seems very likely that the acceleration of innovation would have occurred elsewhere in Europe, probably in France. |